Procrustes analysis

In statistics, Procrustes analysis is a form of statistical shape analysis used to analyse the distribution of a set of shapes. The name Procrustes refers to a bandit from Greek mythology who made his victims fit his bed either by stretching their limbs or cutting them off.

To compare the shape of two or more objects, the objects must be first optimally "superimposed". Procrustes superimposition (PS) is performed by optimally translating, rotating and uniformly scaling the objects. In other words, both the placement in space and the size of the objects are freely adjusted. The aim is to obtain a similar placement and size, by minimizing a measure of shape difference called the Procrustes distance between the objects. Notice that, after PS, the objects will exactly coincide if their shape is identical. This is sometimes called full, as opposed to partial PS, in which scaling is not performed (i.e. the size of the objects is preserved).

In some cases, both full and partial PS may also include reflection. Reflection allows, for instance, a successful (possibly perfect) superimposition of a right hand to a left hand. Thus, partial PS with reflection enabled preserves size but allows translation, rotation and reflection, while full PS with reflection enabled allows translation, rotation, scaling and reflection.

In mathematics:

- an orthogonal Procrustes problem is a method which can be used to find out the optimal rotation and/or reflection (i.e., the optimal orthogonal linear transformation) for the PS of an object with respect to another.

- a constrained orthogonal Procrustes problem, subject to det(R) = 1 (where R is a rotation matrix), is a method which can be used to determine the optimal rotation for the PS of an object with respect to another (reflection is not allowed). In some contexts, this method is called the Kabsch algorithm.

Optimal translation and scaling are determined with much simpler operations (see below).

When a shape is compared to another, or a set of shapes is compared to an arbitrarily selected reference shape, Procrustes analysis is sometimes further qualified as classical or ordinary, as opposed to Generalized Procrustes analysis (GPA), which compares three or more shapes to an optimally determined "mean shape".

Contents |

Ordinary Procrustes analysis

Here we just consider objects made up from a finite number k of points in n dimensions. Often, these points are selected on the continuous surface of complex objects, such as a human bone, and in this case they are called landmark points.

The shape of an object can be considered as a member of an equivalence class formed by removing the translational, rotational and uniform scaling components.

Translation

For example, translational components can be removed from an object by translating the object so that the mean of all the object's points (i.e. its centroid) lies at the origin.

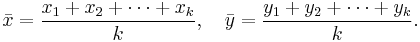

Mathematically: take  points in two dimensions, say

points in two dimensions, say

.

.

The mean of these points is  where

where

Now translate these points so that their mean is translated to the origin  , giving the point

, giving the point  .

.

Uniform scaling

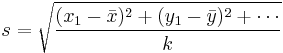

Likewise, the scale component can be removed by scaling the object so that the root mean square distance (RMSD) from the points to the translated origin is 1. This RMSD is a statistical measure of the object's scale or size:

The scale becomes 1 when the point coordinates are divided by the object's initial scale:

.

.

Notice that other methods for defining and removing the scale are sometimes used in the literature.

Rotation

Removing the rotational component is more complex, as a standard reference orientation is not always available. Consider two objects composed of the same number of points with scale and translation removed. Let the points of these be  ,

,  . One of these objects can be used to provide a reference orientation. Fix the reference object and rotate the other around the origin, until you find an optimum angle of rotation

. One of these objects can be used to provide a reference orientation. Fix the reference object and rotate the other around the origin, until you find an optimum angle of rotation  such that the sum of the squared distances (SSD) between the corresponding points is minimised (an example of least squares technique).

such that the sum of the squared distances (SSD) between the corresponding points is minimised (an example of least squares technique).

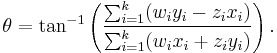

A rotation by angle  gives

gives

.

.

where (u,v) are the coordinates of a rotated point. Taking the derivative of  with respect to

with respect to  and solving for

and solving for  when the derivative is zero gives

when the derivative is zero gives

When the object is three-dimensional, the optimum rotation is represented by a 3-by-3 rotation matrix R, rather than a simple angle, and in this case singular value decomposition can be used to find the optimum value for R (see the solution for the constrained orthogonal Procrustes problem, subject to det(R) = 1).

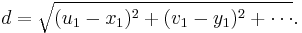

Shape comparison

The difference between the shape of two objects can be evaluated only after "superimposing" the two objects by translating, scaling and optimally rotating them as explained above. The square root of the above mentioned SSD between corresponding points can be used as a statistical measure of this difference in shape:

This measure is often called Procrustes distance. Notice that other more complex definitions of Procrustes distance, and other measures of "shape difference" are sometimes used in the literature.

Superimposing a set of shapes

We showed how to superimpose two shapes. The same method can be applied to superimpose a set of three or more shapes, as far as the above mentioned reference orientation is used for all of them. However, Generalized Procrustes analysis provides a better method to achieve this goal.

Generalized Procrustes analysis (GPA)

GPA applies the Procrustes analysis method to optimally superimpose a set of objects, instead of superimposing them to an arbitrarily selected shape.

Generalized and ordinary Procrustes analysis differ only in their determination of a reference orientation for the objects, which in the former technique is optimally determined, and in the latter one is arbitrarily selected. Scaling and translation are performed the same way by both techniques. When only two shapes are compared, GPA is equivalent to ordinary Procrustes analysis.

The algorithm outline is the following:

- arbitrarily choose a reference shape (typically by selecting it among the available instances)

- superimpose all instances to current reference shape

- compute the mean shape of the current set of superimposed shapes

- if the Procrustes distance between mean and reference shape is above a threshold, set reference to mean shape and continue to step 2.

Variations

There are many ways of representing the shape of an object. The shape of an object can be considered as a member of an equivalence class formed by taking the set of all sets of k points in n dimensions, that is Rkn and factoring out the set of all translations, rotations and scalings. A particular representation of shape is found by choosing a particular representation of the equivalence class. This will give a manifold of dimension kn-4. Procrustes is one method of doing this with particular statistical justification.

Bookstein obtains a representation of shape by fixing the position of two points called the bases line. One point will be fixed at the origin and the other at (1,0) the remaining points form the Bookstein coordinates.

It is also common to consider shape and scale that is with translational and rotational components removed.

Examples

Shape analysis is used in biological data to identify the variations of anatomical features characterised by landmark data, for example in considering the shape of jaw bones.[1]

One study by David George Kendall examined the triangles formed by standing stones to deduce if these were often arranged in straight lines. The shape of a triangle can be represented as a point on the sphere, and the distribution of all shapes can be thought of a distribution over the sphere. The sample distribution from the standing stones was compared with the theoretical distribution to show that the occurrence of straight lines was no more than average.[2]

See also

- Active shape model

- Alignments of random points

- Biometrics

- Generalized Procrustes analysis

- Image registration

- Kent distribution

- Morphometrics

- Orthogonal Procrustes problem

- Procrustes

External links

- Extensions to continuum of points and distributions Procrustes Methods, Shape Recognition, Similarity and Docking, by Michel Petitjean.

References

- ^ "Exploring Space Shape" by Nancy Marie Brown, Research/Penn State, Vol. 15, no. 1, March 1994

- ^ "A Survey of the Statistical Theory of Shape", by David G. Kendall, Statistical Science, Vol. 4, No. 2 (May, 1989), pp. 87-99

- F.L. Bookstein, Morphometric tools for landmark data, Cambridge University Press, (1991).

- J.C. Gower, G.B. Dijksterhuis, Procrustes Problems, Oxford University Press (2004).

- K.V. Mardia, I.L.Dryden, Statistical Shape Analysis, Wiley, Chichester, (1998).